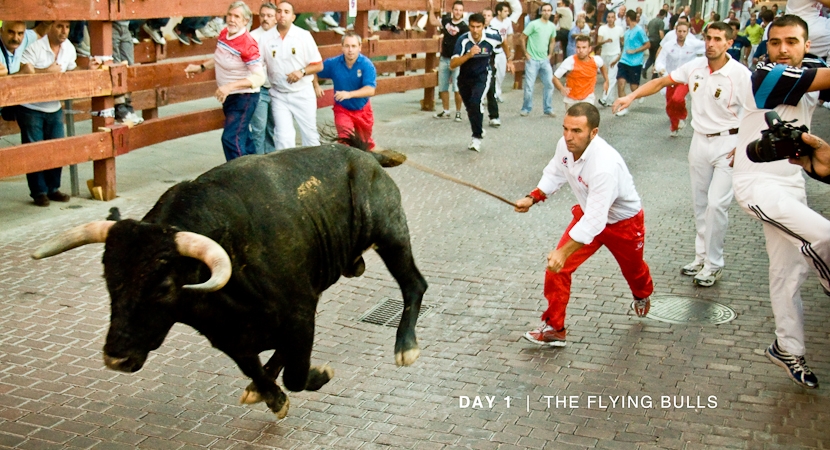

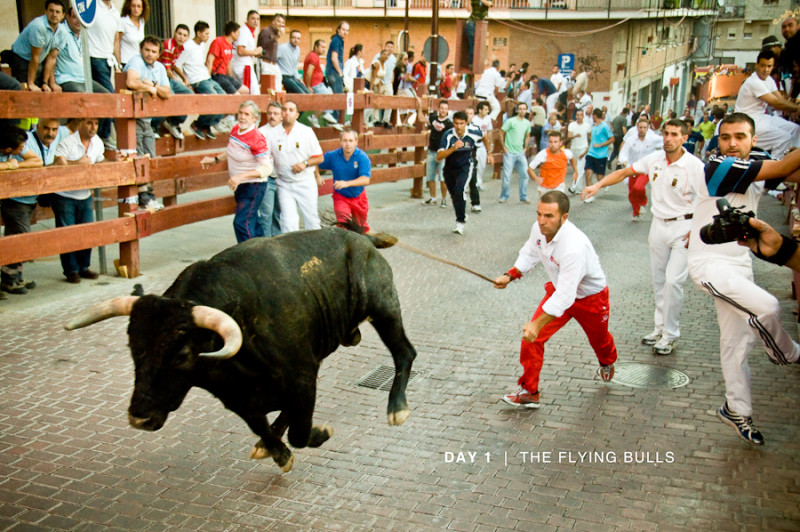

The annual Festival of Saint Fermin, more commonly known as the Running with the Bulls, is held in Pamplona, Spain over an nine-day period. This year, the festival is currently underway and scheduled to end on July 14th. If you are unaware of the festival’s main attraction, it is six aggressive Spanish Fighting Bulls being let wildly loose to rummage and chase scores of adrenaline-hyped participants through the town’s streets. Often resulting in countless injuries from being gored by the bulls, the festival has also reported 15 fatalities since 1924. Made popular by Ernest Hemmingway in his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises as well as his 1932 tale Death in the Afternoon, it has since become Spain’s most well known bull-running fiesta.

The festival is wrought with controversy, however, mainly from Animal Rights organizations. As with most tourism and entertainment activities involving animals, people are often unaware of what happens behind the scenes. PETA lists the alleged mistreatment of the Pamplona bulls on their website, and if true, it is hard to ignore. Like other entertainment activities involving captive animals, tradition is beginning to run into resistance from passionate activists who are able to use social media to help raise awareness.

Photo By Camilo Rueda López. CC BY-ND 2.0

https://instagram.com/p/43uBokINwW/

This Spanish tradition originated in the early 14th Century in the Northeastern part of Spain. Herders transporting farm animals to the market would hurry their cattle by inducing fear and excitement thereby making the animals run wild on the streets. Not soon after, young men would await these occurrences to run with the bulls while attempting to avoid being gored by the horns. Since then, the popularity of running with the bulls spread to other cities in Spain until eventually, it was integrated with an annual festival honoring Saint Fermin in Pamplona, Spain.

https://instagram.com/p/43-J88p3RA/

Attracting tens of thousands of people from all over the world, the nine-day festival is also highlighted with a 24-hour street party. The joyous crowds then converge on the streets for the daily morning run led by six bulls. Bill Hillmann, a Chicago-based writer authored a book, Mozos: A Decade Running With the Bulls of Spain, which he crafts from over 10 years of experience dodging the dangerous creatures. A decade where he himself nearly lost his life to a bull. Hillman describes to The Atlantic the magnetism of joining this fiesta even if it means risking one’s limbs and life. “It’s evolved [for me]. In the beginning, it was just pure adventure, wanting to have that rush and experience it. My first year I ran three days, and someone talked me into watching from a balcony. When I was watching from the balcony, below me, one of the most horrible, bloody mornings unfolded, like directly below my balcony that I was watching from. As I was watching a bull, it began to gore a man right under my balcony.”

After that, Hillman witnessed a unique act of heroism unfolds. “Everyone in the street was suddenly trying to stop the goring, trying to distract the bull, get him away from the guy, but no one could get him away until this one runner showed up named Miguel Angel Perez, who’s a legend…he grabbed hold of the bull’s tail, and when he did that the bull stopped killing this guy. It just sort of started looking back trying to get Miguel. The man crawled away, and the bull followed the man across the street, who was bleeding. And the bull was still trying to get him, but Miguel just held onto the tail and kept the bull from getting him. Miguel led the bull away up the street and out of sight.”

https://instagram.com/p/461b6VhRSs/

Hillman, like many others who have participated the festival realized that there is more to it than the pure adrenaline rush “There’s like a code of ethics, a camaraderie, there’s a sense of brotherhood, there’s a sense of putting yourself at risk to save someone else.” he adds.

Mirroring Hemmingway’s dissection in recognizing the purity of Spain’s bullfighting culture by associating it with the ‘fellowship of the aficionados’, the thousands of people who congregates in the city of Pamplona every year to go racing with the bulls believe share a kinship that transcends even through the controversies it creates with Animal-rights activists.

The controversy surrounding the mistreatment of the bulls may be having an effect on attendance, as participation has dropped nearly 20% since 2012, according to sanfermin.com. The Pamplona Tourism Division blames the steep decrease in attendance to the scheduling of the festival during busy weeks when many tourists may have other plans. As the festival is happening now, it will be interesting to see if this year’s attendance numbers continue the steady decline, and more importantly, if the festival will be able to survive the ever growing chorus of critics amid declining revenue.

Editors Note – I personally disagree with the treatment of the Pamplona bulls, and would like to see an end to the alleged practices used. Whether or not this festival can occur in the same manner with humane treatment of the animals is something I can’t comment on. What I do hate is the position that these festivals cause for us travel writers and photographers. I love that the city of Pamplona and the country of Spain are internationally recognized for having a popular festival that generates millions of dollars for the tourism industry, that in turn, helps local businesses and families. After all, that’s what we do here at Resource Travel. We try to fuel the tourism industry and help our readers discover the world’s most remarkable destinations. But I hate that the attention the festival receives and financial gain it brings to the city and country may come from the mistreatment of animals. So what to do? How can you end the alleged mistreatment while retaining the excitement and revenue that the Running of the Bulls generates? I do not have those answers, unfortunately. I wish I did. But my job as a writer and editor is to provide all sides of the story and let the reader make their own decisions.

We would love to know your thoughts on this controversial matter. Is the treatment of the bulls inhumane? If so, how do you think the festival and it’s positive aspects can live on without the alleged mistreatment? Let us know your opinions in the comments, and please, keep all discussion civil.

Michael Bonocore, Editor-In-Chief