The first thing most people say to me when I first tell them I have lived and worked in Antarctica is, “There is no way I could live down there; it’s way too lonely and isolated.” This is a popular misconception. And we don’t live in fear of polar bears. That’s the wrong pole. Quite to the contrary, Antarctica is a very social little world. Us residents are packed in by twos (sometimes even fours) into crowded dormitories, share a common cafeteria, and we all hit the same drinking hole on the weekends. The only times I truly felt the isolation was when I craved a Big Mac, longed for a Netflix binge with a cat on my lap, or missed yet another close friend’s wedding.

These large icebergs get trapped in the sea ice that forms annually in McMurdo Sound. In a trip out to the sea ice to profile cracks and document unsafe areas, we stumbled upon some of these giant formations and took a few moments to enjoy their beauty.

That same feeling of isolation from the “real world,” however, was the exact reason I came to love Antarctica so much. It was refreshing to be disconnected, and this often promoted self-reflection and development. It’s a self-inflicted, technological exile. The closest things to cell phones were 90’s era Motorola pagers. Wi-fi is reserved exclusively for science traffic much of the year, and there is always a wait for one of the limited number of internet-connected computers in a very public kiosk. After a stretch of time, anything that exists outside the square mile of ice and snow we inhabit is a distant memory referenced only on holidays when you dial a ludicrously long number to reach your loved ones back in the United States. No texts, no Instagram, no SnapChat (I still don’t even know what that is), no Hulu. It sounds like a Millennial’s nightmare, but for me, it was a creative dreamland. I was surrounded by like-minded people, musicians, crafters, painters, woodworkers, metal smiths, all creating in their respective fields and brilliant in their ability to turn nothing into something.

Nacreous clouds (a product of earth’s pollution and a contributing factor to ozone holes) can only be seen under very rare circumstances in the polar regions. They are far and away one of the most beautiful natural phenomena I have ever witnessed, rivaling auroras with their mother of pearl opalescence and brilliant moving shapes and colors. This was a particularly vibrant day and there was a stark contrast of the oranges against the dark silhouette of the hill and the iconic Our Lady of the Snows Shrine, a memorial erected for a lost Seabee who’s tractor fell through the sea ice during the initial construction of McMurdo.

These pressure ridges are formed as the flows of annual sea ice interact and collide from the currents underneath. They create impressive structures and tall sheets of ice fragments that resemble a mini mountain range. Their beauty is only dwarfed by the active volcano, Mount Erebus, smoking in the background.

While on the 500px global photo walk last year, we took advantage of the mild weather and went to the pressure ridges near New Zealand’s Scott Base. Mountaineering axes are used for safety and to check crevasse depth while traversing the area. Lead Mounatineer and fellow photographer Alasdair Turner climbs an ice sheet to retrieve an axe that was lodged into one of the pressure ridges.

Without your face buried in an iPhone, quick or reliable access to the internet, or the constant drone of a television, your mind starts to clear and it’s a great time to assess your life. This is what happened to me, and I found I was missing a creative outlet.

While I had always been involved in creative activities—sewing, painting, crafting, drawing—it was on the 7th continent that I discovered a passion for photography. Returning to the Ice, as we call it, for my first winter, I found that I had a legitimate excuse to take the plunge and invest in some gear. I enlisted a couple of good photographer friends, handed them my credit card, and let them pick out everything a beginner would need. I ended up on that southward bound flight three years ago with a Nikon D7000, and 18-105 F3.5-5.6, and a sturdy tripod.

What resulted was a large collection of photographs, most no good, a few with promise, and the occasional gem enhanced by the fact that I was fortunate to have an ever-interesting, ever-changing backdrop against which to shoot. Many of the photos in my collection were taken during the winter months, with low-lit skies, or in the pure darkness against which the southern lights, the Aurora Australis, glows its eerie green.

Auroras fill the sky over the road that connects McMurdo to our New Zealand neighbors at Scott Base. Since the show happened during the work day, vehicles were passing back and forth to complete their tasks, seemingly unaware of the light display happening above.

Standing near Scott’s Discovery Hut on Hut Point, Vince’s Cross was erected in 1902 as a memorial to George T. Vince who was the first person to perish in McMurdo sound as part of Robert Falcon Scott’s first expedition. Observation Hill can be seen in the distance with faint auroras glowing under the milky way. Lights from McMurdo cast far out onto the flat sea ice and permanent ice shelf.

Before we talk more about the obvious photographer’s subjects—wildlife and landscapes—I do want to mention a little about the work we do down there, because that is itself a subject for endless questions, and is also, as you see, a subject for a few interesting photos.

McMurdo station is like a small city. We are all there for the same purpose: to support science and research. But that looks a little different depending on your skill set.

McMurdo is the largest inhabited location on the continent and needs everything that a regular town would need, from janitors and chefs to doctors and plumbers. It’s a place where electricians find challenging work in their own field, liberal arts graduates drive forklifts, and PhDs wash dishes. If you’re willing to push yourself into trying something new, working long hours 6 days a week, and can learn to adapt to often grueling environmental conditions, it’s a great place to spend a few months. For a photographer, it’s a great place to spend a few years.

While not the most beautiful photo, I like this one because it is so quintesentially McMurdo. This shot was one of my “McMurdo Postcard” series and shows the center of station, an area we call “Derelict Junction”. It is a common meeting place and pickup area for those traveling to the ice runway (15 miles away on the ice shelf) via shuttle vans or our famous “Ivan the Terrabus”. You can see the blue, main building, 155, in the background and the brown corner of the “Gerbil Gym” (named so because of it’s stationary cardio equipment). The tall post on the left houses lights that designate the weather conditions so it is easy to assess the severity of a storm temperature or wind speed by which colored lights are illuminated (on a calm day such as this one, referred to as “weather condition 3”, no lights are used).

With only one mountaineer for the winfly season (a short 6 week season between winter and summer when the station prepares for incoming science groups) volunteers from other departments are often needed to assist with sea ice profiling and marking safe routes from the base to research areas. On this particular day, we were flagging a path for the science groups to follow. This entailed drilling holes into the hard ice for each bamboo pole with a colored flag attached to the top. These flag lines are used on any route, walking or driving, outside of station. They not only serve to keep us on a safe path (away from invisible crevasses) but also make sure we don’t lose our way during bad weather or blowing snow.

A view from one of our industrial dryers looking out into the main station laundry facility. This picture is included because it shows the interesting juxtaposition of our pristine environment outside next to the more gritty reality of maintaining an aging research base at the end of the earth.

The PistenBully is a track vehicle that is often used when science groups or science support teams have to leave station. It is a rugged machine made for the challenges of traversing un-groomed snow and ice and does it’s job well, although it is far from a comfortable ride.

Being a self-contained town, McMurdo has it’s own wastewater treatment plant. In the winter, when the population is at it’s lowest (140s), they are able to shut down each of the trains and clean out the sludge and volcanic dust that accumulates in the pits. It’s a dirty job and volunteers from all over station are trained to help.

While this appears to be an evening shot, it was actually taken in the middle of the day with a bright full moon illuminating the dark dead of winter. The PistenBully travels across a route that is used for search and rescue trainings as well as a recreational hiking and skiing trail. This time it is being used for a morale trip carrying people out to see a favorite Antarctic landmark, Castle Rock.

Even the most amateur photographer will find that Antarctica provides a rich environment, from its 24 hours of sunlight during the summer to the glow of bright full moons of winter, to the seemingly interminable sunrises and sunsets in between. The magic golden hour light shines for full days at a time. Seals bask in the warmth of the sun on the ice shelf, whales play in the frigid and rough sound, and sometimes penguins explore the rocky shoreline.

Due to the nature of the hard ice and packed snow around McMurdo, I had never seen penguin tracks until this day. The recently frozen sea ice had a light dusting of snow which made the perfect canvas for the individuality of each emperor’s tracks. Each one has a different stride and a unique zig-zag line created by the bottom of their tail feathers.

We stumbled across this seal-made hole while profiling the sea ice and could hear the maker moving around underneath the water. With a little patience and a quick burst of photos I was able to catch this little guy taking a breather.

That all sounds wonderful, of course. But for me, when I think of shooting in Antarctica, what immediately comes to mind are the immense challenges it presents. The most obvious and most difficult is that you are constantly fighting against elements that are determined to win. If it’s not the bitter cold wind stinging your eyes and throat, then it’s the dangerous game of fumbling with your camera settings through insulated gloves or—and this is tricky—daring to take them off for a few desperate seconds and risking a touch to the bare metal of your tripod or camera. Bare metal will reach temperatures well below freezing and if you aren’t careful, you can get immediate contact frostbite. The only incident I had in four years was when I got overzealous shooting the wreckage of Pegasus (a military plane that crashed in the permanent ice shelf in 1971). My entire hand got dangerously cold, but my pinky finger got the brunt of it, and to this day, I don’t have feeling in the tip.

Another challenge for me was a lack of motivation. Once winter sets in full force, when you’re living in perpetual darkness, stuck in that same square mile, it starts to be more than just monotonous. Weeks, months would go by where my camera sat forlornly in the corner. I knew I should be taking advantage of this amazing opportunity, but the desire to stay warm won out over my creative guilt and the camera moved from a corner to a drawer.

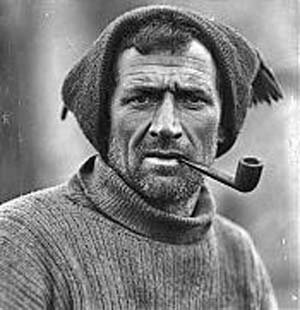

But once in a while during those long months, someone would ask me to photograph something. Sometimes it was just to capture events going on around town. Sometimes it was to collaborate on a project or have photos to send home. I liked these opportunities because it pushed my comfort level and got me shooting an aspect of Antarctica that wasn’t as stereotypical as penguins and seals. One project that was suggested by a friend was to recreate the famous portrait of early Antarctic explorer Thomas Crean. Crean wintered over in 1915 and capturing his distinctly Antarctic look seemed like an interesting way to connect our winter crew with the one that came 100 years earlier. It started out as a small project, since it was my first attempt at “studio” (I use that term loosely) photography. I hung a blanket in the back room of the galley (what we call our dining facility; the word that hangs around from the days when the Navy ran McMurdo) with some makeshift soft boxes made out of cardboard and sheets. Over the course of four sessions, I captured images of over 100 winterovers, pipe and all.

The original photo of Tom Crean and a sampling of the 100+ portrait recreations I took for the 100 year anniversary of the famous Antarctic winterover’s portrait.

Another project involved creating postcards, of a sort. Antarctica brings to mind images of pristine isolation, floating icebergs in perfectly blue water, sunsets over ice. This is what most postcards in our tiny store reflect. But the reality is that our little space of land is covered in gritty volcanic rock and older buildings that, while functional, are not visually appealing. It’s a makeshift town, often hobbled together by the ingenuity of hardworking folks who keep the town running to support science.

So, I created a photography series depicting some of the most mundane scenes. One shot, entitled “McMurdo skyline,” shows a tangle of electrical lines all conjoining over a decrepit old smoking hut in the center of town. My favorite of this series is “Entrance to 155,” showing nothing more than a doorway into an old building. While these photos don’t paint the most beautiful picture of our little slice of heaven, they do represent a more accurate portrayal. Antarctica is not glamorous. While some of us are lucky to see a penguin on occasion (many do not), the reason we are there is to help further scientific endeavors. We work hard and we care about the mission, despite what some news articles would have you believe.

The large blue building referred to only as “155” is entered be everyone on station at least once a day. It houses the station store, barber shop, radio station, craft room, galley, atm, offices and a large portion of first year dorm rooms. It is iconic to the Mcmurdo landscape and endeared by many.

A view inside Cape Evan’s Hut, the headquarters for Robert Falcon Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition 1910-1913. The hut is still full of the early explorers’ belongings, all carefully preserved and maintained by the Antarctic Heritage Trust. This bedside on one one man’s bunk shows the basic toiletries of the times along with some unused stamps, twine and reading material.

Another shot inside the Cape Evan’s Hut. Scientific research was important to Robert Falcon Scott, and there was an entire area inside the little hut dedicated to furthering his study of Antarctica. Here are some of the team’s leftover instruments and tools.

A rusty lantern rests on the main table in Cape Evan’s Hut. Several old photographs show the early expedition men gathered around this table for midwinter celebrations, a winterover tradition since the early years that is still observed today. Midwinter is celebrated on the winter solstice as an acknowledgment that the darkest part of the winter has passed and the sun is now on it’s way to returning to the 7th continent. You can see the rickety bunks in the background, strewn with photos and belongings of those pioneering men.

Another shot from inside Robert Falcon Scott’s Cape Evans hut. The building is full of artifacts and pieces of history that have sat on the continent for over 100 years.

The hardest part about photographing wildlife is finding wildlife. The rare occasion to see a penguin or a whale can sometimes stop tasks midstream. People will drop what they are doing, pop their heads outside, and remember for a moment why they went to Antarctica in the first place; and as much as I loved shooting penguins or seals, I loved putting the camera down and just enjoying the moment even more. If Antarctica taught me anything, it’s that you should always appreciate the journey to get the shot just as much as you appreciate the shot itself.

Bradley Geer contributed to this article.

See more from Kira Morris on her website, Facebook, and Instagram.

There are strict rules outlined in the Antarctic Treaty not to interfere with animals or disturb their environment. So when I saw this Emperor on the permanent ice shelf halfway between station and the ice runway I laid down with my camera as still as possible and just waited in the snow. As if on cue he waddled straight into my frame and, in a serendipitous moment, raised his wings for a perfect pose in front of Mount Discovery, a peak in the Royal Society Range which runs across the other side of the Ross Ice Shelf.

Cracks in the newly formed sea ice provided a perfect place for this seal to emerge onto the shore at Hut Point. This had been a very active day for wildlife and the seals were no exception. They played in the shallow ice water for most of the afternoon while Emperors explored the same area.

As the sea ice starts to form with the coming of winter, penguins have to move further away from McMurdo to stay near open water. You can see the distinct edge of the sea ice in this shot, however by the next day the ice had expanded it’s territory and this was the last group of emperors we saw before the darkness set in.

As the pressure ridges on the sea ice break off and make way for open water, some are inevitably left behind. This seemingly out of place formation is the only remaining evidence that the bay was filled with dramatic ice ridges only a few weeks before. A group of Emperors enjoy the makeshift shoreline and easy access to water that the sea ice provides.

These emperors arrived late in the season, close to the start of winter. There is a small cove called Winter Quarters Bay at the edge of the station and this group of penguins came in from feeding to walk around on the recently formed sea ice and send everyone running with their cameras. I had the lucky vantage point of being slightly higher and was able to snap some close up shots without the penguins noticing my presence.

Water and wind move the newly formed sea ice around Hut Point and create these piles of ice fragments where the ice meets the shore. This lazy seal had come up through a crack and was content to be covered in a light layer of falling snow while he lay there for hours.

This Adelie penguin was in his final stages of molting and had spent a few late summer days here on Hut Point (near Robert Falcon Scott’s Discovery Hut) sheltering from the wind. Within a few weeks the water in the background would freeze over, the sun would disappear for four months and this little guy would leave McMurdo for a spot nearer to the new ice edge.

This is my favorite Antarctic self portrait. I was hiking on one of our recreational trails circling station and had to peel my eyelashes apart to get the shot because they had frozen closed in mere minutes.