All too often, I find myself asking the question, ‘Why am I taking this photo?’

Is it to freeze a moment in time to share with others? Is it to preserve a feeling or celebration? Is it to increase attention to a cause? Is it to add to my professional portfolio? Is it because I am being paid? Or, is it spontaneously unknown? Every photographer responds differently and for me, the answer may be all of the above. Regardless of the reason we capture images, one astounding purpose should be to self-critique with the goal of improving our craft and artistry that fuels us all to keep growing.

It has been almost two years since I traveled to Kenya for a 16-day medical mission trip with David Beyda, MD to capture the great work of him and his medical team. As a non-healthcare member on a medical mission trip, I knew my contribution and focus would be different, but my passion and dedication the same as everyone else. After landing in the capital city of Nairobi, we traveled two hours to the southern city of Kajiado, which is the equal distance from the Tanzanian border, for the first 6-day leg of the medical mission. Each day, we would set out for a new village from our base camp for a 16-hour day. After ending the first leg of the trip, we bid farewell to half of our team, but not until we spent two days at the Masai Mara National Reserve for a safari experience. All of a sudden, my medical colleagues and I shared a passion – photography! The remaining team and I journeyed north to the Turkana region, a geographic vault to the beginnings of humankind, which borders Ethopia for the final leg of our Kenyan trip.

It has been almost two years since I traveled to Kenya for a 16-day medical mission trip with David Beyda, MD to capture the great work of him and his medical team. As a non-healthcare member on a medical mission trip, I knew my contribution and focus would be different, but my passion and dedication the same as everyone else. After landing in the capital city of Nairobi, we traveled two hours to the southern city of Kajiado, which is the equal distance from the Tanzanian border, for the first 6-day leg of the medical mission. Each day, we would set out for a new village from our base camp for a 16-hour day. After ending the first leg of the trip, we bid farewell to half of our team, but not until we spent two days at the Masai Mara National Reserve for a safari experience. All of a sudden, my medical colleagues and I shared a passion – photography! The remaining team and I journeyed north to the Turkana region, a geographic vault to the beginnings of humankind, which borders Ethopia for the final leg of our Kenyan trip.

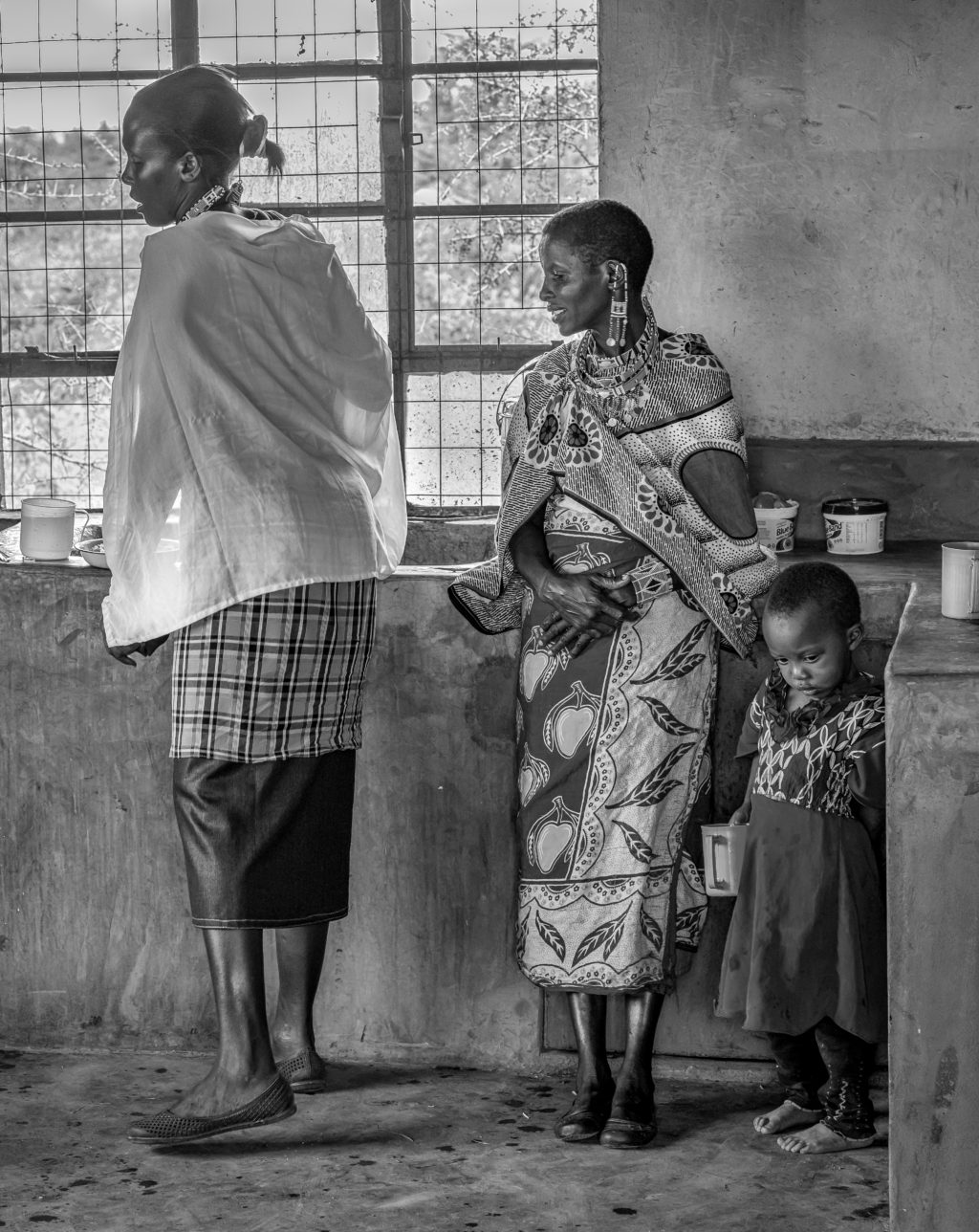

Regardless of the medical clinic location, my goal was to tell the stories of the patients, the hardships of limited (or no) access to basic healthcare services, the victories of winning the trust of a young child and her mother, and heartbreak of disease progression that a cycle of antibiotics would have altered long-lasting (and often irreversible) effects. During the clinic days, every sense was firing as I experienced and observed unconditional love, respect, trust, hurt, teamwork, sadness and joy through my camera. My days did not end until I edited and wrote in my journal which pushed me through every form of exhaustion possible. I am often asked how I was able to compartmentalize my emotions, especially as a father to three children, and I proudly share that my job was not to feel sorry or guilty for my life compared to those with whom we were treating. When photographing life and human stories, there is a delicate line of respect and exploitation, and the use of the image determines the intention. My photography served two purposes: create a collection for Dr. Beyda and one for myself.

In November 2017, I had a public gallery showing of a small selection of my private collection from Kenya and found myself reliving the raw emotions of each and every moment. As I described the images to the community onlookers, my mind played as a Hollywood-created flashback scene; I was back in the environment, traveling two-hours (one way) on the dustiest, bumpiest roads that took our team into remote villages outside of Kajiado for day-long clinics. I felt the sweltering heat and unforgiving sun in Turkana, which barely cooled for our night’s sleep on an exposed concrete slab under the safety of a mosquito net. I felt the joy from the countless encounters with bright-eyed curious children who found interest in my tattoos, who shared smiles and giggles before rushing to see their image on the camera’s digital display. Recounting these stories resurfaced intense emotions and reminded me of my trip’s purpose: bring awareness to the work of the medical mission through human connection and compassion.

These images are now displayed in my dining room. Admittedly, there is a sense of guilt experienced while we crowd around the table to share a holiday feast, discuss the newest iPhone or an upcoming vacation as juxtaposed to a wall of images that represent the lack of clean water or basic health care services and limited nutrition; however, the placement allows me to revisit the images every day as I walk about my home. I study the composition. I study the emotion. I study the use of natural lighting. I study my art. I study my craft. And I find there is much to learn, grow and improve.

I challenge all photographers to push beyond a project’s completion after post-editing, archiving and delivery to our clients. In all, Dr. Beyda received more than 3,000 edited images and I kept a private collection of fewer than 300. Print your images and study them. Connect with them. Grow from them and not just for the craft, but to be a better human. You do not need a public gallery show to share your work with friends and family – have one in your home. Display your work for your children to observe, to strike a meaningful conversation about needs versus wants, talk about cultures, traditions and values from others’ perspectives. Ask your child to describe what they see and enjoy your work from a whole new angle.

Why did I take photographs in Kenya? I took them to revisit a place that I will forever cherish for the kindness, gratitude, friendship and devotion to a human connection with a guy from Fort Worth, Texas.

Brandon Cunningham, founder of Snap Judgement Photography, is a travel photographer who seeks to enrich understanding, tolerance and diversity with an eye towards story-telling through street and portrait work. Read his article about a photography adventure through India. He lives in Fort Worth, Texas and can be followed on Instagram at @snapjudgementphoto.